- Home

- Madeline Smoot

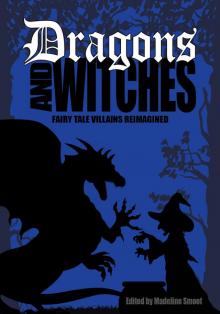

Dragons and Witches

Dragons and Witches Read online

Dragons and Witches:

Fairy Tale Villains Reimagined

Edited by Madeline Smoot

Text Copyright © 2017

Forest Image Copyright © shutterstock.com/Baksiabat

Dragon Image Copyright © shutterstock.com/ patrimonio designs ltd

Witch Image Copyright © shutterstock.com/Novi Elysa

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without express permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, write:

CBAY Books

PO Box 670296

Dallas, TX 75367

Children’s Brains are Yummy Books

Dallas, Texas

www.cbaybooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-933767-61-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-933767-62-8

Kindle ISBN: 978-1-933767-63-5

PDF ISBN: 978-1-933767-64-2

Burning

C.H. Spalding

I woke to pain.

Pain is holy. It purifies us, relieves us of our sin. When I am grown, my pain will always tear through my body, a symphony of sensation to remind me to focus on the greater good. I am young and have only known the training pain that slowly prepares us for the inward changes when the spikes that rise from our bodies will also pierce us within.

I opened my eyes, saw the wreckage within my escape pod. The world outside was bright and green, loud with a cacophony of voices from abominations. This planet must be new to my people, or we would already have killed them all, all the birds and mammals, and any reptiles longer than the span of my front claws. Insects we usually left alive, and the seas are irredeemable depths of poison sin that not even our fire can cleanse.

My claws hit the controls, sounds alerting me to their status. My beacon had been in a part of my pod that had broken off; it was active, but I would need to get to it to send an actual message. There were no signs that other pods had reached this planet when the ship hull burst. I was alone for now. Perhaps for the rest of my life.

My middle left leg was dislocated, and I pulled it back into position. If it did not heal correctly, I would have to amputate, but not yet. The planet had plenty of nitrogen and hydrogen in its atmosphere, and there is little carbon based that my people can’t digest. I could reasonably expect to survive here, long enough to wait for rescue and to choose my path if it did not come.

The pod was crushed badly. If I’d been full-grown, I would have had to leave limbs behind to leave at all, but I had only recently had my full naming. My exoskeleton was scratched and dented in places but not breached. I worked to keep it that way as I flipped upside down and clung to the wall and scurried out the broken view port.

The world outside was worse than I had imagined. Dozens of winged creatures took to the air as I emerged, and a herd of small herbivores startled and ran. There was profligate life everywhere I looked. I could work my whole life and not make a dent in it.

I caught a snake from a nearby tree in my jaw and devoured it, more because I needed the protein than that I had already begun my hopeless, holy work. If my people came and found me, we would work together to consecrate this world. If not …

The sensors around my ears allowed me to triangulate on the beacon. In a civilized world, with food contained to vats, it would have been a brief journey. Through this wilderness it could take days.

I slithered through the underbrush as best I could, using my limbs to clear obstacles. The herbivores startled at my approach, and I hadn’t the time or the energy to waste in chasing them down. There would be time for hunting later.

The trees formed a canopy overhead, which thinned the growth a little on the ground. It was my first wild world, and I fell into a rhythm that turned to enjoyment—over, under, beside, and onward towards my goal.

Pleasure, of course, is a sin, and it was the highest grace that mine was ended.

The sky opened up in front of me, and I pulled myself to a stop with the help of all six limbs. The green forest ended, and in front of me was only water.

We are the children of fire and blood. We are stronger than pain. From infancy we can squirm through fire unharmed. Falls rarely kill us, and we can continue with all limbs gone. If we live long enough, lost limbs will grow back. Our death is usually inherent in our bodies; we burn out from our own fire or are torn apart from within. Water is less our foe than the absence of what we are. Our fire cannot burn in it. Our bodies cannot take in nitrogen and hydrogen from it. Our exoskeletons do not allow us to stay atop it.

The water in front of me extended beyond the limits of my sight. If there was a land bridge across, it too lay beyond the limits of my sight, either to North or to South. Since the beacon still worked, it had to be on dry land, but it would have been far easier to cross the vacuum of space than the poison depths in front of me.

I threw objects in to try to assess the depth. Stones fell, wood floated, and the small mammal I flung in could swim. It was at least three times my length deep, and it likely got deeper as it went further from shore.

I shrugged my limbs back in against my body. I could think as I went, and one direction was as promising as the other. I headed North.

In that first despair, I would have been tempted to make my choice without thought, just to burn everything in my path. I was too young for fire, just as I was too young for blood. I had to grow to full size, grow to the time of my choice. Instead I continued to slither north. As rescue grew more unlikely I ate more of the creatures I encountered.

The sun set and a trio of moons rose, shifting light that was enough for my purposes. By the time the sun rose again the beacon was becoming faint, and I reluctantly turned back. There was still no sign of a way across.

I slowed a little on my way back, cooling my thoughts. If I were a mammal, I might be able to swim. If I were made of wood, I could float across if the wind and water let me.

Back at my starting place I paused and considered, then set about gathering what I needed.

The first time I threw a small mammal at a floating piece of wood I missed, and it drowned. The second time I threw too hard, and either killed it or knocked it unconscious against the wood. Either way, it drowned. The third time, the animal reached the wood and scrabbled aboard but, once there, was helpless to control the movement of the branch.

I used different sizes of wood, different animals to fling after them. Most just held on as the wind and water carried them … somewhere. Eventually one clever creature clung to the wood while kicking at the water with its feet as though steering. I was so impressed that I hesitated to kill it when it returned to shore. That moment was all it needed to escape, and I accepted this sin with my others. Mercy is a great weakness.

I calculated as best I could, then pulled a fallen tree to the edge of the water. I grabbed hold with my front claws and pushed off with the back ones. The tree trunk rolled in the water, and I scrambled to stay afloat. Dying like this would not cleanse my sins.

There would be glory for my people if I succeeded in my quest. My head would join the ancestors in the Hall of the Exalted if this crossing led to my rescue and the taming of this world.

I let this thought warm me as I headed out into the endless sea.

Some creatures sleep, but my kind does not. We may reach a place of reverie or contemplation, but we remain aware and in control of mind and body. It was a day later when I at last followed the beacon to shore. My claws pushed against stone below the water, and I hauled the tree trunk with me up onto dry land.

The beacon was close now, and I looked for signs of it even as I caught a bird between my jaws, then another in my front claws. My carapace was itching, certain sign that I was growing.

At last I found the

beacon on the forest floor, lit by the hole it had rent in the canopy above. I opened it carefully with front claws and teeth, then activated its sensors.

The beacon’s range was far more than my headset, but there was no other energy signature on this planet or in the space around it. I was truly alone. I thrummed my breath to calm myself, then set the beacon to record my message.

“This is Ez-Kotii of the 192nd cohort. This world is ripe with abomination, and no others of our kind are here. Let the histories show that I crossed a day’s journey of water upon a fallen tree to reach this place. I will grow, and I will seek to cleanse this place. I choose …” My voice faltered for just a moment, and I hit pause. One fire breather could never clear this planet. There really only was one choice. I resumed recording. “I choose the path of blood.”

I set the beacon to broadcast. I would grow, and when the spines pierced me internally as well as extending from my body, I would set my body to carrying life instead of fire. I would nurture my body so that perhaps fifteen, perhaps twenty young would devour me from within on their way out into the world. There would be no one to teach them, only their hunger and later their pain. They would learn. It is what our kind does.

I allowed myself a moment to accept it and then turned back to the forest. It was time to hunt.

The survey ship shifted into the system and took up a distant orbit around the yellow sun. The ensign on Comm alerted the ship’s captain—only a lieutenant, officially—at the energy signature coming from the second planet, a promising looking world with three moons.

“Audio,” the captain ordered, leaning back into her chair. One of the grav-strap buckles dug into her shoulder. It would have to be adjusted. She’d been around, had seen plenty of things, in her years in the service. But she wasn’t used to having this seat. Yet.

The ensign had complied. Momentarily a rasping, hissing, musical sound filled the bridge, a minor key in quarter tones.

“It’s old,” the ensign said. “A century, at least. Are we going down?”

The captain shook her head. “Not when you hear that. Never when you hear that.”

The ensign blinked in surprise, looking up from his controls. “Do you know what it means?”

“Close enough.” The captain checked her sensors; land-based animals were severely limited on the planet, although the seas teemed with life. “It means, ‘Here Be Dragons.’”

C.H Spalding has been writing since the 80’s, though only dared make submissions professionally in the last few years. Most of those published have been in science fiction or fantasy, and currently there are several young adult novels sitting around unfinished. Spare time is usually taken up by children, pets, artwork, and watching too many documentaries on YouTube.

A Very Baba Yaga Halloween

Joy Preble

Baba Yaga sat by the fire in her hut in the forest. The flames heated her ancient bones as she rocked and dreamed and planned, her iron teeth glinting in the firelight. On her lap, her huge hands rested, gnarled fingers twining. When she desired hot sweet tea to quench her thirst, one hand detached from her wrist and scuttled down her leg to the floor, thick nails clattering on the wood as it went to fetch her drink.

It was nice to be a witch. Nice to have the power. Occasionally a too thin child stuck between her teeth. But why quibble? She was Baba Yaga. These things sometimes happened.

Underneath the hut, two enormous chicken legs scrabbled the earth, carrying her house this way and that. No predators could find the mighty Baba Yaga unless she willed it to be. Lost boys and girls might stumble upon her, but everyone knew what happened to them. Eaten. Ground to dust in the witch’s mortar, crushed into nothingness by the same pestle with which she stirred the air as she flew.

The wise Death Goddess. The Bone Mother.

Today, though, a small worry gnawed at her like she would often gnaw a stray child’s leg bone. Halloween was coming. All Hallow’s Eve. The night that spirits rose and walked the earth and things that went bump in the night showed themselves as solid and real as the humans who ran from them.

“Do not worry, Mistress,” her three horsemen—one red, one black, one white—told her. “You are the mighty Baba Yaga. The Wild Crone. You hold dominion over all. What is one silly night? Foolish humans dressed in foolish costumes, pretending to be something they are not. Bah!”

It was a silly holiday, she agreed. But something in the horsemen’s words stuck with her anyway. Baba Yaga had never appeared as anything but herself. She tapped her huge chin with one enormous hand. What would it hurt, if for one night, she became something else?

The thought careened through her brain as thoughts sometimes do.

Yes. She would do it.

From under her rocking chair by the fire, her cat mewed loudly, threading its way around the scrape of her roughened ankles. In the fire, the bones of the lost traveler she had eaten for breakfast knocked against the huge logs, the fatty aroma from the remaining scraps of flesh drifting like the finest of perfumes.

Here was the question, as curious as that brat Vasilisa who had bested her by relying on the tiny magic doll she kept in her pocket. The girl who had been sent into the witch’s forest to get fire and who had lived. Baba Yaga admired Vasilisa as much as she despised her.

What did a witch become when she chose to wear a costume?

Baba Yaga rocked and sipped her hot sweet tea.

What indeed? Did she dare? Would she be so bold?

Yes.

She would go as what she once was—a beauty who had sold her looks for power. She would dance and sing and remember.

Yes.

And then, she would eat her fill of those pesky trick-or-treaters. There was nothing like second hand licorice taste.

“How many days until Halloween?” she asked the red horseman even though she knew the answer. It was nice to hear him say it anyway. Hear him obey her command to tell.

He bowed, his muscular body a lithe, human hook, then rose with a graceful flourish of his hands. He had thick, muscular thighs, a brush of a moustache, and dark, golden eyes. If he had a name, he knew better than to tell her. Names held power. She already held his.

“A fortnight,” the red horseman told her.

Two weeks. Creeping on their own near the fire, her disembodied hands clasped bony pinkies and danced.

Three days later, Baba Yaga had finished the perfect dress, frothy midnight blue silk and periwinkle ribbon and lavender organza, lovely folds and ripples of material, perhaps a bit broader and higher in the neckline than she once used to wear. It hung perfectly on her, cosseting her every curve and line. Sure, a dress could be conjured by magic, but something in the process pulled at her. She was rarely sentimental, but rarely did not mean never. This dress. She had dreamed of this dress once upon a time. Now she had created it.

She might have finished sewing faster, but she was distracted on the first day by two lost hikers, a boy and a girl. The boy gasped, a hard choking sound, as he realized that the smooth white nobs on top of the fence posts were skulls, empty and staring. “Run,” he told the girl as his eyes went wide with fear. “Run!”

But it was too late. Baba Yaga’s enormous left hand was already scuttling swiftly into the yard, and even as the pair turned, it gripped tight around the girl’s ankles, ripping her from the boy’s grasp and sending her sprawling to her knees. The gate snapped shut, invisible locks clicking into place.

“Ohhhh,” shrieked the girl. “No. Let go. Help me. Ohmygod, Harper, get it off me.”

Baba Yaga stepped into the doorway, snapping the forefinger and thumb of her still-attached hand. “Come!” she said. The hand gripping the girl’s tender flesh released itself.

The Bone Mother debated. She wasn’t always good. Wasn’t always evil. She lived a life with no moral or immoral absolutes, just pleasant, murky grey areas that made things interesting. Maybe she’d kill them. Maybe she’d let them go. Or reward them in some way, although Baba Yaga wasn’t big on t

hat particular surprise. But the trick was this: Nothing her captives would do—nothing any of them ever did—made any difference. Not prayers or deeds or supplications. Only that nettlesome Vasilisa and one other girl had ever found a way out. Since then, Baba Yaga had been much more careful.

Still. Each visitor posed a new adventure.

“Do you know how to stitch beads onto the hem of a gown?” she asked the girl. Her free hand had skipped through the dirt and was working its way up her dress and into her flapping, empty sleeve.

The boy gagged and then threw up, yellowish bile and specks of half-digested granola bar spattering his clothes. Harper. That’s what the girl had called him. Clearly Harper was not cut out for such adventures.

“Do you love him?” Baba Yaga asked then. Her attention had already moved from the question of embroidery.

“I …,” said the girl. “I … who are you? What is this?” Her voice quavered but unlike her companion, she did not lose her lunch. She struggled to her feet. Her knees were raw and bleeding.

The witch licked her lips.

“You have answered neither of my questions, dear,” said Baba Yaga. She made her voice gentle and low. This always confused her captives quite deliciously. “Do you have a name, my child?”

The girl managed a glance at the boy, who was wiping his mouth with the back of his hand while tears trickled down his pasty cheeks. His eyes had gone wild and unfocused.

“I can sew,” she said. “My mother taught me.” She straightened her posture and held Baba Yaga’s gaze. This time, the witch barely heard the tremble in her voice.

“Can you now?”

A slight nod.

The girl, nameless still, had not confessed to loving or not loving the boy. Smart, thought Baba Yaga. Clever girl. She licked her lips again. Clever girls usually tasted spicy, a fleshy mixture of cayenne and salt and the finest of smoked paprika.

“You’re a witch,” said the girl. “Aren’t you?”

The boy was trying to run, but his feet would not move. More precisely, Baba Yaga was not letting them. He wind-milled his arms to no particular effect. In other circumstances, the motion would be comic. Actually, in this circumstance it was rather amusing, she had to admit.

Dragons and Witches

Dragons and Witches